Problems With Current Value-Based Payment Systems

Why “Pay for Performance” Hasn’t Worked

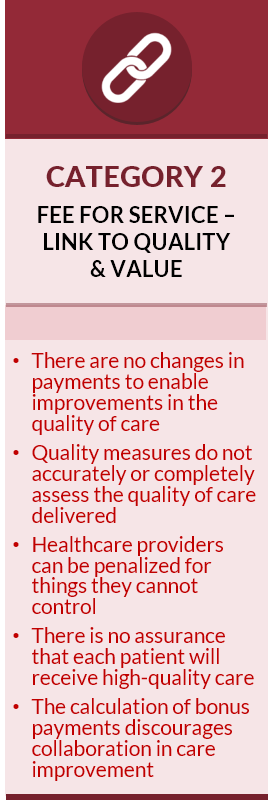

The most common approach to value-based payment has been “pay for performance” (P4P). Under this approach, a healthcare provider may receive bonus payments if it performs better than other providers on a set of payer-defined measures of quality, utilization, or spending, and it may have to pay penalties or have its payments reduced if its performance is lower than what other providers achieve on these measures. Most physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare providers now participate in at least one pay-for-performance system because of the P4P programs created in Medicare, such as the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) for physicians, the Hospital Value-Based Purchasing Program, and the Skilled Nursing Facility Value-Based Purchasing program. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) describes this as “Category 2: Fee for Service with a Link to Quality and Value” (in contrast to “Category 1: Fee for Service - No Link to Quality & Value”).

This approach has been unsuccessful in improving the quality of care for a number of reasons:

- There are no new fees for services that could improve the quality of care. Physicians, hospitals, and other healthcare providers are still paid only for the same types of services they are paid for under the standard fee-for-service system, and they still lose money if they deliver care in different ways or help patients stay healthier.

- Payments fall short of the cost of delivering quality care. Even if a healthcare provider qualifies for a performance-based payment, the amount is typically too small to make up the shortfall between fee-for-service payments and the cost of delivering high-quality care. Moreover, the administrative burdens associated with quality measurement can cause a provider’s costs to increase more than the additional revenue it receives from performance-based payments.

- The measures used do not accurately or completely assess the quality of care delivered. Quality is assessed based on whether the care for a patient met a general standard of quality, even if meeting the standard would have been undesirable or harmful for that particular patient. Moreover, because quality measures are only applicable to a narrow range of health conditions and services, there is no measure of quality at all for many types of health problems and patients.

- A healthcare provider can be penalized for reasons outside of the provider’s control. For example, if a patient is unable or unwilling to use all of the services needed to achieve a good result on the quality measure (e.g., the patient cannot afford the medications needed to treat their diabetes), the provider will be scored as having failed on the measure for that patient and the provider’s payments may be reduced, even though the provider had no control over the factors affecting that patient’s adherence. In many cases, a provider who treats a patient for one health problem can be penalized based on the quality of care that unrelated providers deliver for completely different health problems.

- There is no assurance that each patient will receive high quality care. A healthcare provider is paid for delivering an inappropriate or poor quality service to a patient regardless of how the provider scores on quality measures. In fact, since performance-based payments are based on the percentage of patients whose care met the standard in the quality measure, a provider would be paid more for delivering poor-quality care to an individual patient if the provider has higher-than-average quality scores for its other patients.

- The payments discourage collaboration in care improvement. In many P4P programs, such as Medicare’s Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), a provider can only receive a bonus payment for good performance if other providers have been penalized for poor performance. This discourages collaborative efforts to improve care, because if a high-performing provider helps other providers to improve, the high-performer will receive a smaller bonus.

It is often suggested that P4P systems have been unsuccessful because the “incentives aren’t large enough,” but the real problem is that P4P doesn’t actually solve the problems with fee-for-service payment. Moreover, the simplistic quality measures used in these systems can discourage providers from delivering care to disadvantaged patients who have complex needs or difficulty adhering to standard approaches to treatment.

Fortunately, there is a better approach to value-based payment: Patient-Centered Payment.

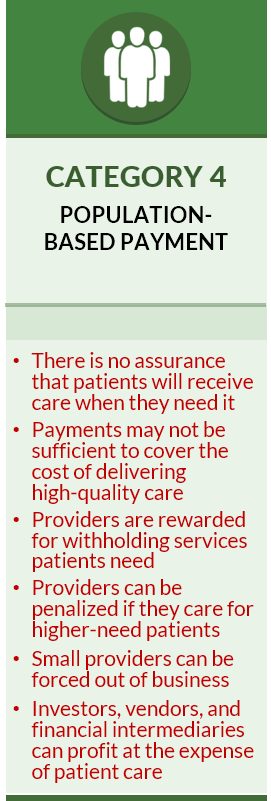

The Problems With Population-Based Payment

“Population-based” payment systems do not pay fees for individual services, but instead pay a healthcare provider a fixed amount each month to provide a patient with as many services as the patient needs. The payments are referred to as “population-based” because the total amount of revenue a provider receives depends on the number of patients the provider is caring for, not how many services or what types of services are used to treat the patients.

Population-based payments are fundamentally the same as traditional capitation payments except that (1) the payment amounts may be higher for individual patients who have more chronic conditions, and (2) the average payment amounts may be adjusted up or down based on measures of quality or spending similar to pay-for-performance and shared savings programs.

A single monthly payment for each patient gives a healthcare provider greater flexibility to deliver different services and a more predictable revenue stream than paying fees for each individual service delivered, and it also makes it easier for a patient or payer to predict how much they will need to pay for care. However, this approach fails to solve all of the problems with current fee-for-service payment systems, and it also creates new problems that do not exist under fee-for-service:

- There is no assurance that patients will receive care when they need it. A strength of fee-for-service payment is that a provider is only paid if they deliver a service to a patient. In contrast, under population-based payment, the provider is paid regardless of whether a patient receives the services they need.

- Payments may not be sufficient to cover the cost of delivering high-quality care. Most proposals for capitation and population-based payments set the payment amounts at levels designed to generate the same amount of revenue the provider has been receiving from fee-for-service payments, and in some cases less. This means that if the fee-for-service revenue was inadequate to cover the cost of high-quality care, it is likely that the capitation payments will also be inadequate.

- Providers are rewarded for withholding services the patient needs. Capitation payments are the same regardless of how many services are delivered or what types of services are delivered. However, the provider will incur higher costs when more services are delivered, and the provider will save money when fewer services are delivered, so even if the payment is large enough to support all of the services the patient needs, the provider’s profits will be higher if fewer services are delivered. The small number of simple quality measures used in these payment models does nothing to protect against most potential types of undertreatment.

- Providers can be penalized for providing care to higher-need patients. One of the strengths of fee-for-service payment is that providers will be paid for providing additional services to patients who have more healthcare problems. In contrast, typical population-based payment systems make no adjustments in payment for patients with new chronic conditions, for patients with multiple acute problems, or patients who need more or different services because they face non-medical barriers to care. This can penalize providers who care for high-need patients.

- Providers can be penalized for factors beyond their control. In “global” or “comprehensive” population-based payment systems, a physician practice or health system is expected to pay for all of the services a patient needs from the fixed population-based payment. The provider may have little or no ability to control many of the factors that affect the cost of those services, such as increases in the prices of drugs or services that have to be delivered by other providers or health systems. This can further discourage caring for patients who have higher needs and create even stronger incentives to withhold necessary but expensive treatments.

- Investors, vendors, and financial intermediaries can profit at the expense of patient care. Because of the high levels of financial risk associated with population-based payment systems, healthcare providers are forced to pay vendors and consultants to help them identify ways to maximize profits and minimize losses, which reduces the revenues available for healthcare services to patients. Private investors and financial intermediaries can make bigger profits on the fixed capitation payments if they can find ways to cherry-pick patients and increase the risk scores assigned to patients, rather than by improving the quality of healthcare services.

Fortunately, there is a better approach to value-based payment: Patient-Centered Payment.

5 Fatal Flaws in Total Cost of Care and Population-Based Payment Model

What is Needed to Make Value-Based Payment Successful?

The failure of current value-based payment programs to significantly reduce healthcare spending has resulted in proposals to (1) require providers to take “downside risk” for all of the services their patients receive, and (2) completely replace fee-for-service payments with “population-based payments.”

There is no evidence that requiring providers to take financial risk for the total cost of care or replacing fees with capitation will be more successful than shared savings models in controlling spending while maintaining quality. In fact, there is good reason to believe these types of programs would cause more problems than they solve because of five fundamental flaws in the ways such programs operate:

- The budgets and spending targets that are used will always be wrong;

- Providers don’t receive adequate funding for care of higher-need patients;

- The quality measures that are used don’t protect patients against undertreatment;

- Providers have no greater ability to deliver high-value services than under standard fee-for-service payments; and

- Patients don’t have a choice about whether to participate.

Five Fatal Flaws in Total Cost of Care and Population-Based Payment Models

1. Budgets and Spending Targets Will Always Be Wrong

An essential component of total cost of care and population-based payment models is a budget, target, or “benchmark” for the total amount that can be spent on all of the healthcare services a group of patients receives. If a physician group, health system, or Accountable Care Organization (ACO) participates in the payment model, it is penalized if the actual spending on its patients is above that budget/target, and it is rewarded if the spending is lower. (In a population-based payment or capitation system, physicians, hospitals, and other providers are expected to deliver all of the services their patients need in return for a fixed payment per patient; the budget for a group of patients is simply the amount paid per patient times the number of patients.)

Three different methods have been used to establish these budgets and spending targets, each of which has serious flaws:

- Method 1: Trend from the Past. One method sets the budget/target based on a forecast of the increase in spending that will be needed compared to the past. However, as Yogi Berra once said, “it’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” Every year, new drugs and treatments are developed and new evidence emerges about which treatments are most effective; in addition, new diseases like COVID-19 can appear, and unexpected supply or workforce shortages can cause significant increases in costs. These inherently unpredictable events will inevitably cause the cost of high-value care to differ from the forecast, potentially by a large amount. CMS has had difficulty forecasting total spending for millions of Medicare beneficiaries (e.g., Part B premiums for 2022 were set based on what is now believed to be a significant overestimate of Medicare spending on the drug Aduhelm), so budgets based on projections for smaller groups of patients are even less likely to be accurate.

- Method 2: Comparison to Other Providers. A second method sets the budget/target at a level below what is spent by providers who are not participating in the risk-based payment model. This method implicitly assumes the non-participating providers are delivering unnecessary or avoidable services and that the providers who are at risk for spending can save money by not delivering similar services. However, if the comparison group of providers has healthier patients or is undertreating their patients, a budget based on their spending will be inadequate. Moreover, it will be difficult to find an appropriate comparison group if most or all providers are participating in the risk-based payment model. (The so-called “rural glitch” in the Medicare Shared Savings Program is caused by trying to compare spending for patients in an ACO to spending on other patients in the community when most of the patients are in the ACO.)

- Method 3: Percentage of Insurance Premiums. The third method sets the budget or target spending for the patients at a percentage of the total insurance premiums their health plan receives for them. Although low premiums help a health plan attract more members, normally the premiums have to be high enough to pay for the healthcare services those members need. However, under a percentage-of-premium arrangement, the health plan no longer has to worry about spending more than the premium revenues it receives. If premiums are too low to cover the costs of the services the plan members need, the providers are penalized, not the health plan.

None of these approaches bases the budget or target on an estimate of how much it would actually cost to deliver appropriate, high-quality care to patients. The Medicare program has always set the fees it pays for individual services based on a detailed analysis of the cost of delivering those services. However, no similar process has been established to determine the right amount of total spending that is needed to deliver all of the services a group of patients will need.

Moreover, the budgets and spending targets in all three methods are increasingly being driven by arbitrary decisions about how much spending is desirable, regardless of whether that is actually feasible for physicians or hospitals to achieve. If a payer wants to spend less money, it can simply increase the annual budget/target by a smaller amount, regardless of the actual increase in the costs of labor or supplies the providers experience, or it can require a larger “discount” without any analysis showing how the reduction in spending could actually be achieved.

2. Providers Don’t Receive Adequate Funding for Higher-Need Patients

Patients with greater health needs require more healthcare services, so spending on these patients will inherently be higher than on other patients. In addition, patients with complex conditions and those who face social barriers to improving their health will require more time and support from healthcare providers, and that will increase the cost of delivering services to them.

Although it is universally agreed that budgets and targets need to be “risk adjusted” in order to address differences in patient needs, current risk adjustment methods fail to do so effectively. For example, under the Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) system used in most Medicare alternative payment models, a patient’s risk score stays the same even if:

- the patient experiences one or more acute illnesses during the year, no matter how much it costs to treat those illnesses;

- the patient is newly diagnosed with a chronic condition, even though the patient will need treatment and assistance in managing that condition (the patient will not receive a higher risk score for the chronic condition until the year after they are diagnosed);

- the patient has a more advanced or complex version of a chronic condition that requires more services or more expensive treatments (the diagnosis codes for many conditions indicate the presence of the condition, but not its severity);

- the patient faces barriers to receiving healthcare services or improving their health, such as poverty, homelessness, illiteracy, lack of access to transportation and fresh food, etc.

If the risk scores don’t increase when patients have greater needs, the budget for their care won’t increase. As a result, the providers responsible for the budget will be financially penalized if a higher proportion of their patients have many acute illnesses, new chronic conditions, or barriers to health. In addition, Medicare places limits on how much the risk scores for a group of patients can increase over time. Although this is intended to discourage providers from recording additional diagnosis codes solely to increase the spending budget, it penalizes providers whose patients develop many new health problems.

3. Quality Measures Don’t Protect Patients Against Undertreatment

A premise of risk-based and population-based payments is that physicians will stop ordering and delivering unnecessary services if they face penalties for exceeding a spending budget/target. Eliminating unnecessary services is desirable because it reduces spending without harming patients.

However, the budgets and targets make no distinction between spending on necessary versus unnecessary services. If the budget is set too low, the only option for avoiding a penalty may be to avoid delivering services that patients need or to use treatments that are cheaper but less effective. In this case, the lower spending does harm patients.

Moreover, in a population-based payment system, a provider is still paid the same amount for a patient even if the patient receives no services at all. If this causes the provider to reduce the number of patients they see or treat, it may be more difficult for patients to access the care they need in a timely fashion.

Contrary to popular belief, the quality measures used in risk-based payment programs do nothing to prevent patients from being undertreated. For example, in the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP), Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) are at risk for total spending on their patients, but:

- there are no measures of whether patients with cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, stroke, or other expensive-to-treat conditions are receiving appropriate care. If ACO patients with these kinds of conditions are given cheaper but less effective treatments, the ACO will be more likely to meet its spending target and there will be no negative impact on its quality scores.

- there is no actual penalty if the ACO performs poorly on any of the quality measures that are used in the program. At most, the ACO would receive a smaller shared savings bonus if it had reduced spending sufficiently to qualify for such a payment. On the other hand, the ACO will be penalized if spending exceeds the target, even if the higher spending was needed to deliver high-quality care.

In population-based payment systems, the payments may be reduced if the providers perform poorly on quality measures. However, quality measures don’t assure that each individual patient will receive high-quality care; the ACO or provider group simply has to have better quality scores on average than other physicians or ACOs.

4. Providers Have No Greater Ability to Deliver High-Value Services

Fee-for-service payment is typically criticized because it “rewards volume instead of value.” However, a bigger problem for patients and providers is the lack of payment or inadequate payment for many high-value services. For example, there are typically no fees for education and proactive care management services provided by nurses, community health workers, and pharmacists, for palliative care services, or for non-medical services such as transportation. In addition, the fees paid for office visits are often too low to allow physicians to spend adequate time with patients who have complex needs. All of this can cause patients to be misdiagnosed or experience poor outcomes that will result in higher spending on their care.

Most risk-based payment models don’t solve these problems because they don’t make any changes in what services are paid for or the amounts paid for those services. Although providers can receive a shared savings bonus if they deliver additional or different services that significantly reduce total spending, that bonus won’t come until long after the services are delivered. Physician practices and other small providers cannot afford to incur additional costs to deliver more services with no assurance as to whether they will receive enough additional revenue to cover those costs.

In theory, an ACO that receives a population-based payment on behalf of its providers (rather than the providers receiving fees for services and shared savings payments) could pay the providers more or differently for their services. However, most ACOs do not have systems for paying physicians and hospitals for services unless they employ the physicians or own the hospitals. Forcing ACOs to establish claims payment systems would not only be expensive but wasteful, since it would duplicate the systems health plans already have in place.

The biggest improvements in care delivery have resulted from the small number of value-based payment programs that explicitly pay more to support the delivery of new services, such as Medicare’s Comprehensive Primary Care Plus program, Oncology Care Model, and ACO Investment Model. Unfortunately, all of these programs have been terminated in favor of more problematic risk-based models.

5. Patients Don’t Have a Choice About Whether to Participate

Most people would likely prefer not to be part of a system in which physicians can (1) be penalized for ordering or delivering treatments their patients need simply because the treatments are expensive, (2) receive a financial bonus for using less-effective treatments because they cost less, or (3) be paid even if they do doing nothing at all to help their patients, particularly if (4) patients in that system are unlikely to receive any more or better services than they would have otherwise. For decades, people have had the opportunity to enroll in HMOs that pay doctors using capitation, but most have chosen not to, and the majority of Medicare beneficiaries continue to enroll in Original Medicare despite the availability of “zero-premium” Medicare Advantage plans.

However, under the risk-based payment systems used by Medicare and many commercial health plans, patients don’t have a choice. For example, in the Medicare Shared Savings Program, a patient is automatically “attributed” or “assigned” to an ACO if the patient receives most of their primary care services from physicians who are part of the ACO, regardless of whether the patient wants to be assigned or not. If a patient is concerned that they could receive less effective treatments because the ACO is required to reduce spending, the only way they can escape assignment is to find a primary care physician who is not part of an ACO or to not seek primary care services at all. This could also cause patients to receive less effective care.

These attribution systems are also problematic for the physicians who are participating in the risk-based payment program, since a single visit with a patient could cause the physician to be held responsible for all of the services the patient received during the entire year, including services delivered before the physician ever met the patient.

The Negative Impacts of Downside Risk and Population-Based Payment

Although proponents claim that downside risk and population-based payments are desirable because they can support “population health” and “coordinated care,” the negative impacts of the flaws described above can easily outweigh any benefits:

- Reduced Access to Prevention and Treatment. Most health insurance companies control their spending by finding ways to deny or delay services, so if they shift risk to providers along with insufficient funding, the providers will be forced to do the same thing. Patients could be placed on waiting lists for services, just as they are in other countries that arbitrarily cap healthcare spending. Preventive services could suffer the most, since they increase costs in the short run but may not produce savings until many years in the future.

- Greater Health Inequities. The patients who are most likely to be harmed are those with the kinds of complex needs and social barriers to health that current risk adjustment systems ignore. These patients already experience worse outcomes, and disparities will increase when payments are not adequate to cover the costs of the services they need.

- More Provider Consolidation. Risk-based payments are biased in favor of large health systems and physician groups. For example, in the Medicare Shared Savings Program, ACOs are required to have at least 5,000 assigned beneficiaries in order to participate, and the most favorable financial rules apply to those with 60,000 or more beneficiaries. Requiring providers to take significant downside risk will force small physician practices and hospitals to close or to consolidate with larger systems, which usually leads to higher costs and lower quality care.

The full extent of these impacts has not yet been seen because most payment models to date have not included significant downside risk. However, the negative impacts could be significant if more physicians and other healthcare providers are forced into risk-based payment models and the levels of risk are increased. Many of the resulting harms will likely be irreversible.

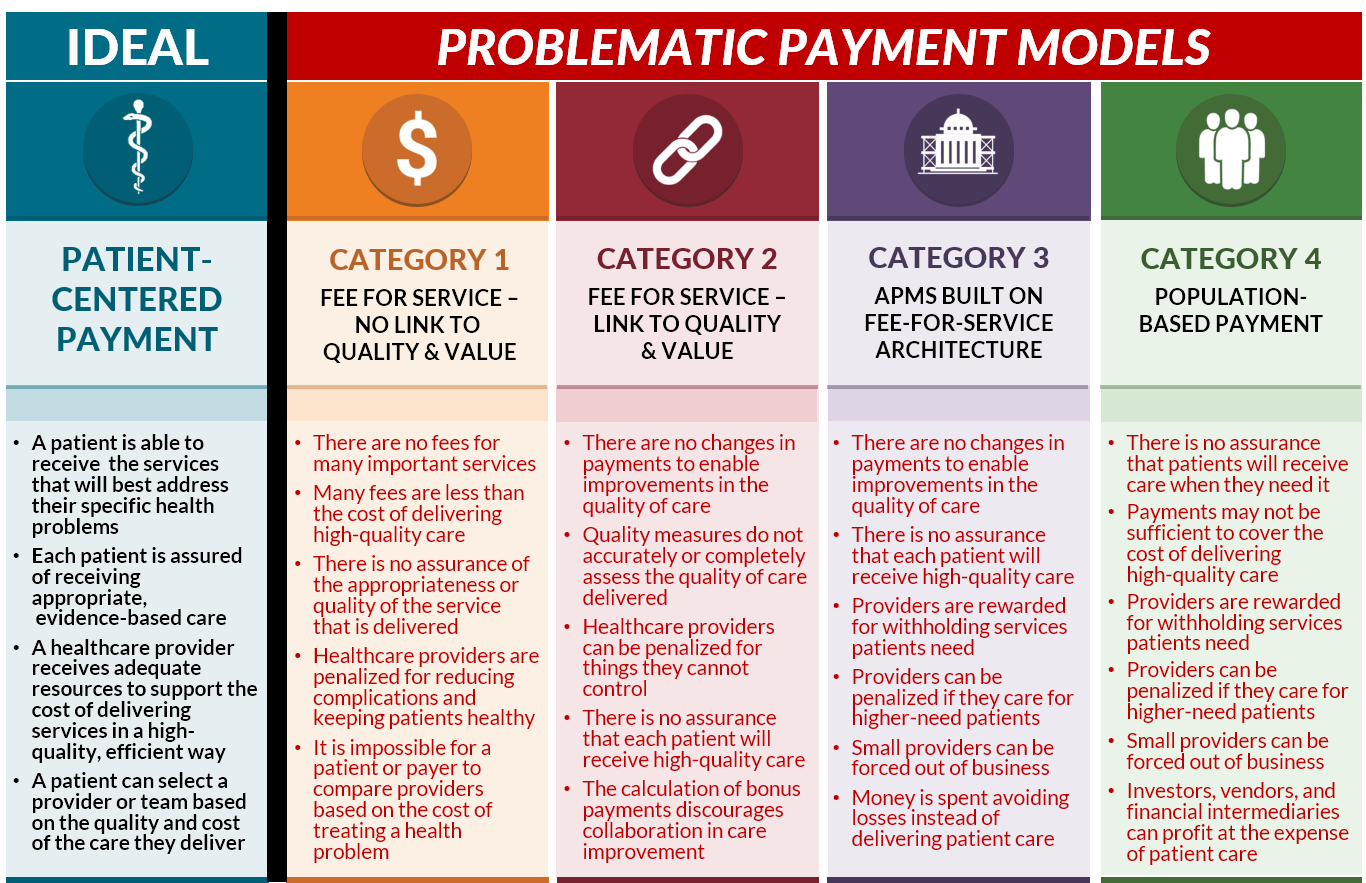

A Better Way: Patient-Centered Payment

Fortunately, there is a better way to implement value-based payment and to support accountable care than simply shifting risk to providers. A Patient-Centered Payment system can solve the problems in current fee-for-service payment systems without reducing access to services or the quality of care for patients. In a Patient-Centered Payment system:

- A patient is able to receive the services that will best address their specific health problems. The current gaps in fee-for-service payments should be explicitly filled, and savings should be achieved by reducing unnecessary and avoidable services, not by forcing physicians to use cheaper, less effective treatments.

- Each patient is assured of receiving appropriate, evidence-based care. Healthcare providers should provide high-quality care for each individual patient, not just provide care that is better on average than other providers.

- A healthcare provider receives adequate resources to support the cost of delivering necessary services in a high-quality, efficient manner. Payments should be based on what it actually costs to deliver good care, not simply what payers would like to spend.

- A patient can select physicians based on the quality and cost of the care they deliver. No one provider or health system will be the best at delivering all of the services an individual patient may need, so patients should not be forced to receive care only from a “narrow network” chosen by a health plan or health system.

Patient-Centered Payment systems with these characteristics have already been developed for primary care, chronic disease care, cancer care, maternity care, and other conditions. They simply need to be implemented by Medicare and other payers.

A pdf version of this article is available for download.

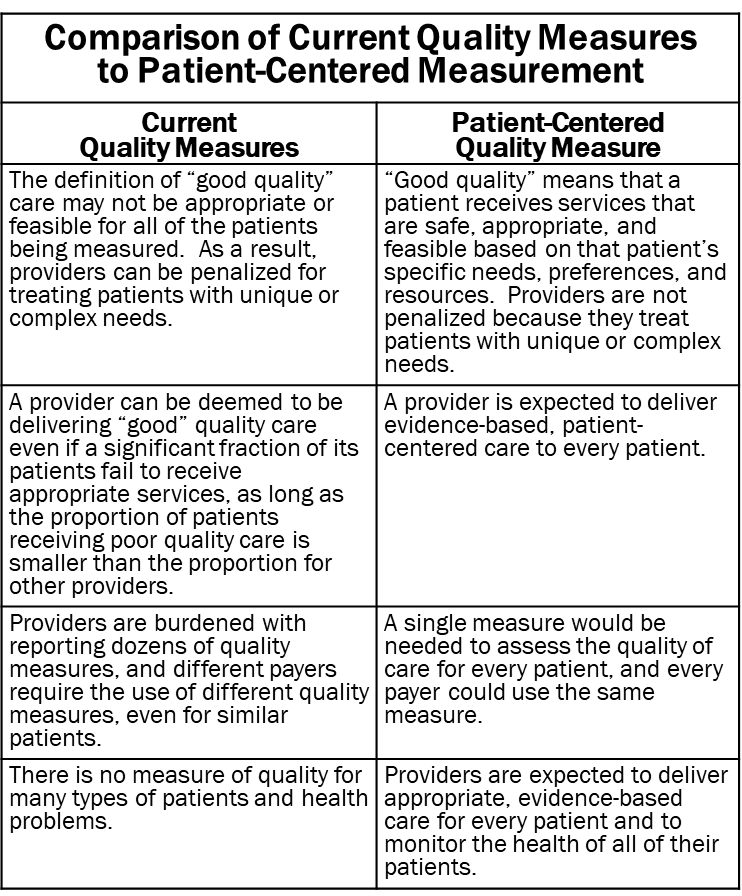

Why Quality Measures Don’t Measure Quality

The Use of Quality Measures in Value-Based Payment

A major weakness in traditional fee-for-service payment is that healthcare providers are paid for delivering a service regardless of the quality or appropriateness of the service. Value-based payment programs have attempted to correct this by paying bonuses or imposing penalties on providers based on various types of quality measures.

These programs assume that higher scores on quality measures mean that patients are receiving higher-quality care. Unfortunately, in many cases, the exact opposite is true. As a result, current quality measures can cause physicians and hospitals to be penalized for providing the most appropriate care for patients and to be rewarded for delivering lower-quality care. This has the potential to exacerbate health disparities rather than improve quality and value.

Example: Measuring the Quality of Diabetes Care

The most commonly used quality measure is the percentage of patients with diabetes whose HbA1c level is above 9.0. HbA1c (glycated hemoglobin) is a measure of the patient’s average blood sugar level. Since high blood sugar can lead to vision loss, kidney disease, and other complications, one of the goals of diabetes care is to keep a patient’s HbA1c levels low. (In the standard version of this measure, a patient is classified as having poor diabetes control if their HbA1c level was above 9.0 the most recent time it was measured or no HbA1c test result was recorded at all during the year for which the measure is calculated. Because population-level quality measures like this are expressed in terms of percentages and HbA1c levels are also typically reported as a percentage, HbA1c levels are discussed below without the % symbol in order to avoid confusion.)

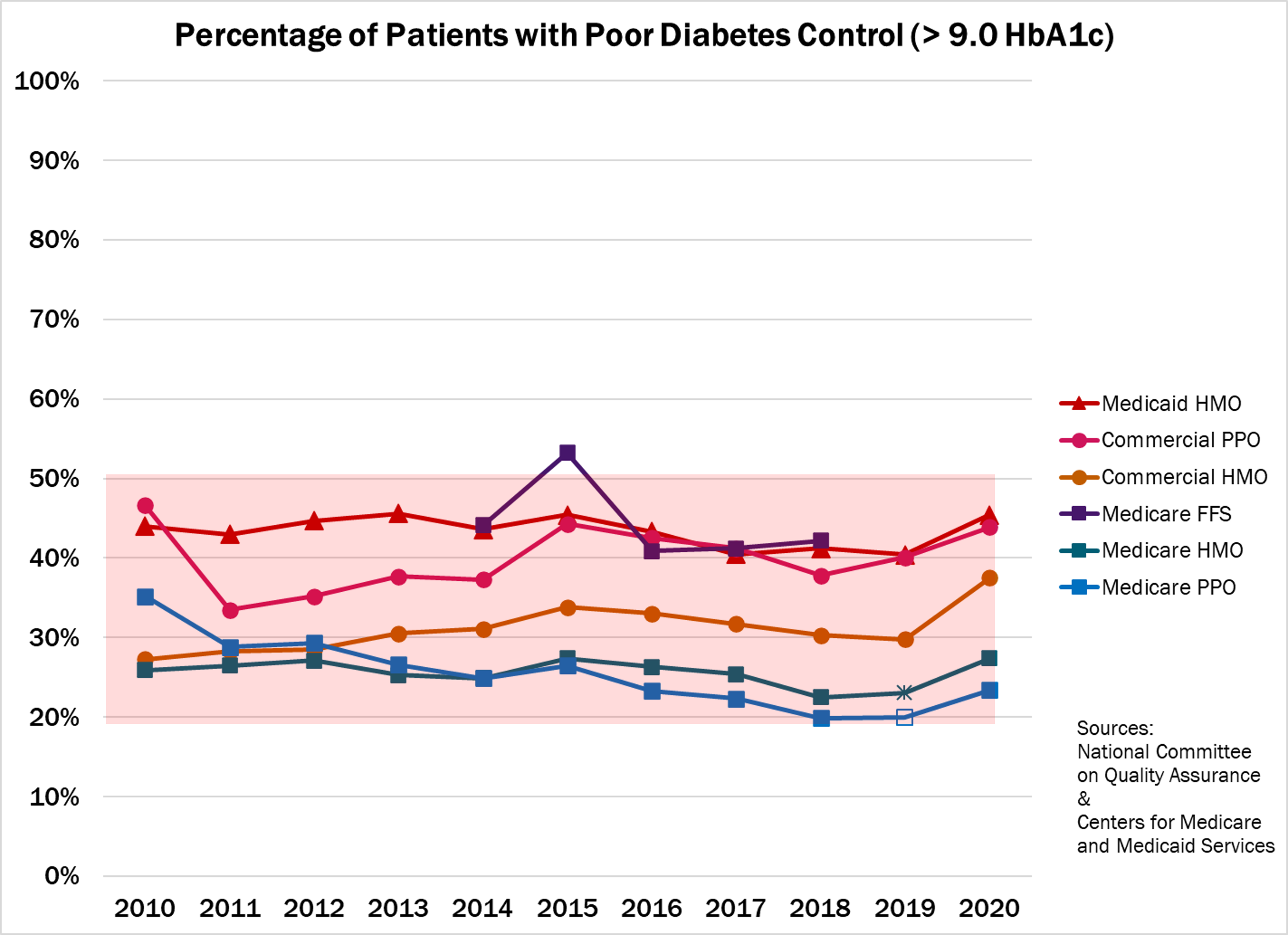

However, despite over a decade of public reporting and financial incentives tied to this measure, the percentage of patients with an HbA1c above 9.0 has remained essentially unchanged. In 2020, between 20% and 50% of the patients in every category of health insurance had high HbA1c levels. The percentages for each type of insurance were almost identical in 2010.

Does this mean physician practices or health plans need stronger financial incentives to improve the care of patients with diabetes? Or is there a problem with the way the quality of care is being measured?

How Current Quality Measures Evaluate Care for Individual Patients

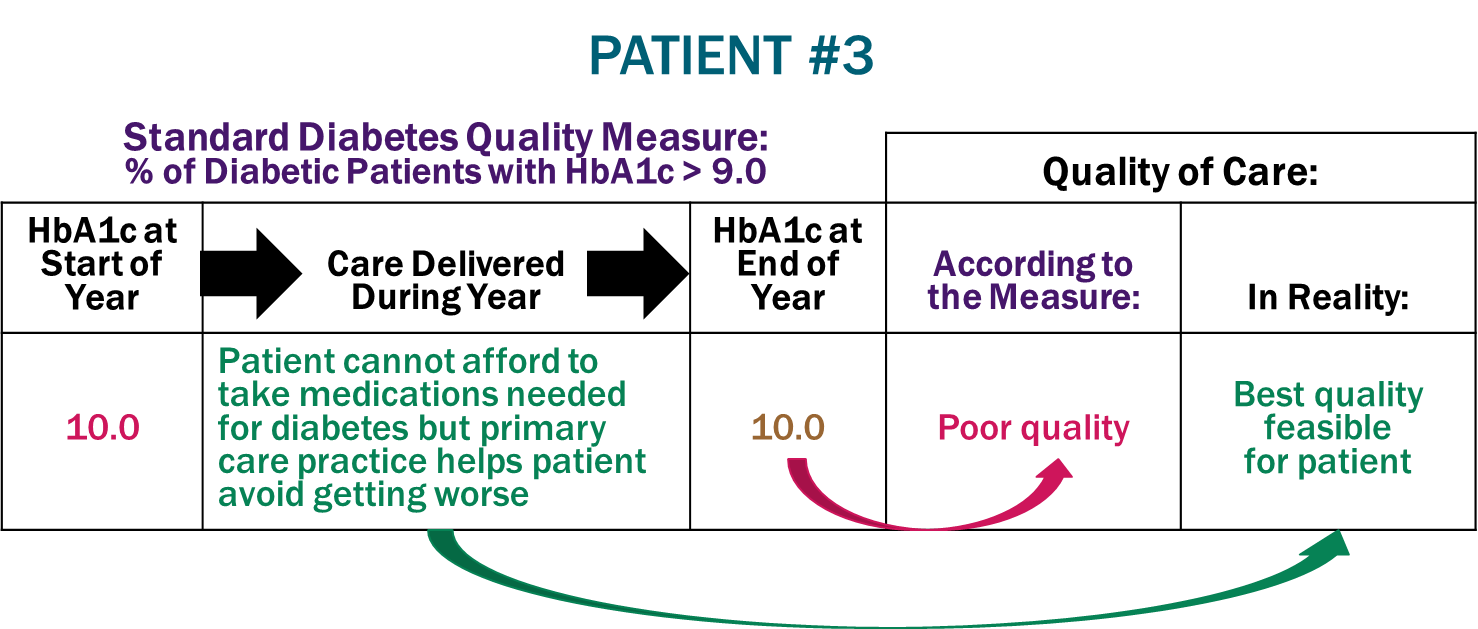

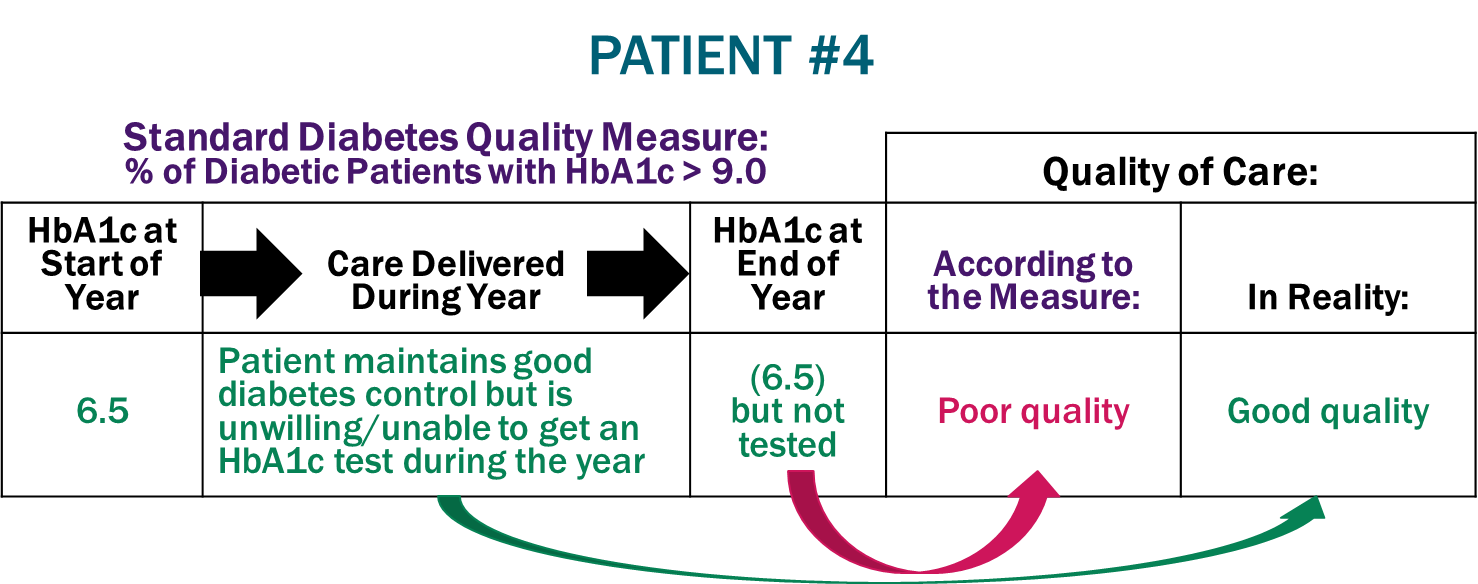

To be meaningful, a quality measure has to accurately assess whether an individual patient is receiving good or bad care. Current quality measures don’t do this. Consider how the diabetes quality measure would rate the care of four hypothetical patients with diabetes who begin receiving care from new primary care physicians:

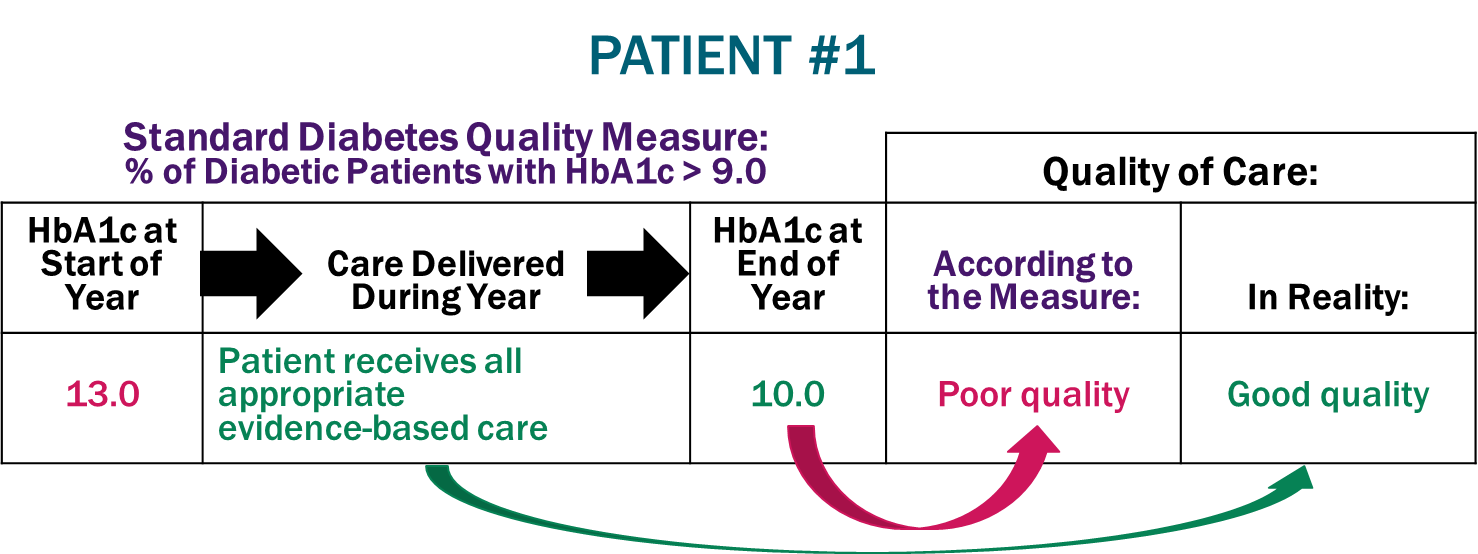

Poor Quality Score Despite Good Quality Care. Patient #1 has a very high blood sugar level (13.0 HbA1c) when they begin seeing their new physician. The physician and practice staff do all of the things that medical evidence has shown will improve control of the patient’s diabetes, such as prescribing appropriate medication and encouraging changes in diet and exercise, and as a result, the patient’s blood sugar control improves significantly (to an HbA1c of 10) by the end of the year. However, for the purposes of the quality measure, it doesn’t matter whether the patient received evidence-based care or how much the patient improved; if the patient’s HbA1c is still above 9, the physician’s care is rated as poor quality.

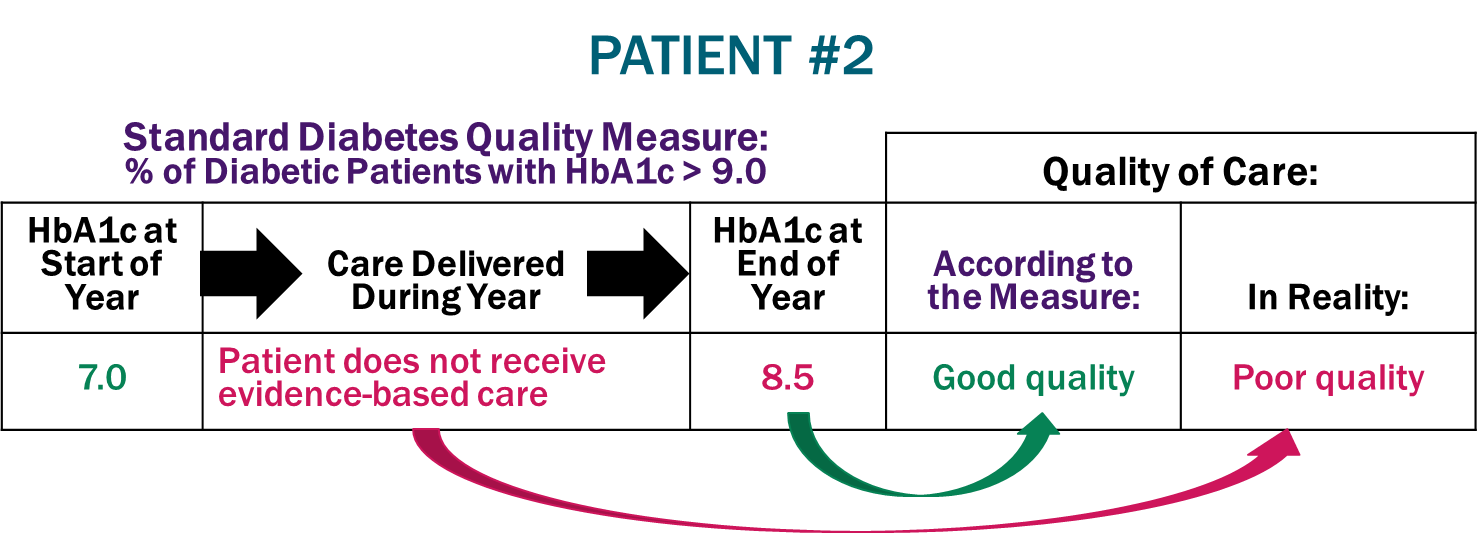

Good Quality Score Despite Poor Quality Care. Patient #2 has a relatively low blood sugar level when they begin seeing their new physician. The physician practice fails to provide the patient with appropriate care for their diabetes, and as a result, the patient’s HbA1c increases significantly. For most patients, the goal of diabetes care is to keep HbA1c levels below 8.0 or ideally below 7.0, so a patient with an HbA1c of 8.5 or 9.0 would not be considered as having “good” control of their diabetes. Under the quality measure, however, the physician’s care is considered “good quality” because the HbA1c level is not above 9.0.

Failure to Adjust for Barriers to Care. Patient #3 has a high blood sugar level when they begin receiving care from their new physician. Although appropriate medications would likely reduce this, the patient cannot afford them (e.g., because they do not have prescription insurance or cannot afford to pay the required cost-sharing). The physician and staff in the primary care practice recommend alternative approaches that are feasible for the patient, such as changes to their diet, and this prevents the patient’s blood sugar levels from worsening. Although the patient received the best care possible with the resources available, the measure rates the care as “poor quality” because the patient’s HbA1c level is still above 9.

Ignoring What Matters to the Patient. Patient #4 has maintained good control of their diabetes for many years and continues to do so with guidance and support from their new physician. Although the practice orders an HbA1c test, the patient doesn’t get tested because the patient monitors their blood sugar regularly and sees no need to spend the time or money to get an HbA1c test that year when they have other health problems of greater concern. However, the formula for the quality measure requires that the patient be classified as having “poor control” if no HbA1c test has been performed, regardless of whether other information indicates their diabetes is being successfully managed.

In all four cases, the quality measure rates the quality of care the wrong way. Good quality care is rated as poor, while poor quality care is considered good, and there is no adjustment for patients who are unable or unwilling to use healthcare services that might have resulted in better outcomes.

How Current Quality Measures Evaluate Care for a Population of Patients

Under value-based payment systems, the quality rating for an individual patient won’t affect how much a provider is paid for its services to that patient. What matters is whether the average quality for the provider’s “population” of patients is better or worse than the average for other similar providers. In fact, a provider can be paid more for delivering poor quality care to an individual patient if enough other patients are rated as receiving high-quality care from that provider.

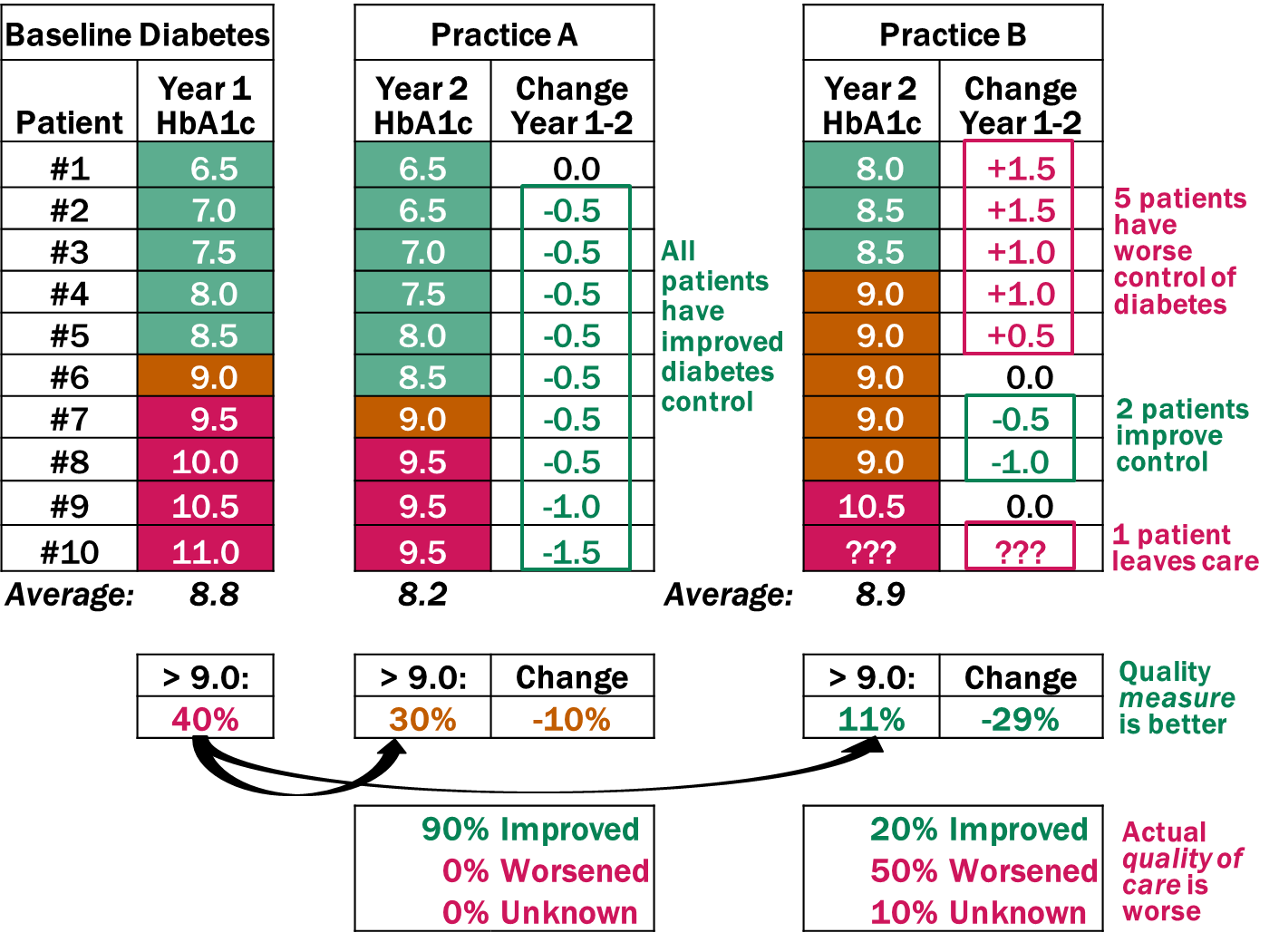

To understand how this is possible, consider two primary care practices, each of which enrolls 10 new patients who have diabetes. At the time they enroll, each group of patients has HbA1c levels ranging from 6.5 to 11.0, and 40% of the patients have HbA1c levels above 9.0.

- Practice A delivers individualized, evidence-based diabetes care to each of the patients, and every patient improves their blood sugar control. By the end of the year, 30% of the patients now have HbA1c levels above 9.0, compared to 40% initially.

- Practice B focuses its attention almost exclusively on the patients with HbA1c levels above 9.0. Two of those patients improve enough that their HbA1c levels are no longer above the 9.0 threshold (although they are still far above a desirable level of blood sugar control), while one patient leaves the practice because of dissatisfaction with their care. All of the other patients in the practice do worse, but their higher blood sugar levels are not (yet) above the 9.0 threshold used in the quality measure. Although the average HbA1c level has increased, only 1 of the 9 remaining patients (11% of the total) has an HbA1c level above the 9.0 threshold used in the quality measure.

Which primary care practice delivered better care to its patients?

It seems obvious that Practice A is doing a better job, since all of its patients received appropriate care, whereas half of the patients in Practice B did not. However, according to the diabetes quality measure, Practice B delivered better-quality care because a smaller percentage of its patients had HbA1c levels above 9.0.

How Current Quality Measures Can Reduce Quality and Increase Disparities

These serious flaws in the way quality is currently measured can cause the true quality of care to decrease rather than improve:

- Steering patients to the wrong providers. In the example above, patients could mistakenly believe they would get better care from Practice B than Practice A. Some patients might even be forced to switch from Practice A to Practice B if their health insurance plan excluded Practice A from its network because of its lower quality score.

- Paying more for lower-value care. Under a value-based payment program that provided financial incentives based on the diabetes quality measure, Practice B could receive a bonus, while Practice A could receive a penalty. Instead of paying less for low-quality care, the payer would actually be paying more.

- Reducing access to care for higher-need patients. It would be easier for a physician practice to get a higher score on the diabetes quality measure by refusing to enroll patients who have poorly-controlled diabetes than by doing the hard work needed to help those patients manage their diabetes successfully. This could make it more difficult for disadvantaged patients and patients with complex conditions to obtain the services they need.

These problems are not unique to the diabetes quality measure. Most of the quality measures currently used in value-based payment programs are structured in similarly problematic ways:

- Arbitrary, simplistic thresholds for “quality.” Most quality measures use a single arbitrary threshold to distinguish “good quality” care from “poor quality” care for every patient. It doesn’t matter whether a patient is getting all of the services they need or whether their health gets better or worse; all that matters is whether the patient is on one side of the threshold or the other when the measure is calculated.

- Failure to adjust for patient-specific needs. Many patients face barriers in obtaining the services needed to achieve good outcomes (e.g., they cannot afford effective medications) or they do not respond well to standard therapies. Yet most quality measures provide no mechanism for either excluding these patients from the measure or adjusting the quality standard to reflect the services or outcomes that are most appropriate for the patients. As a result, care that is customized to the patients’ needs can be classified as “poor quality,” and providers who serve higher-need patients may be classified as delivering lower-quality care.

Because of these limitations, no one actually expects that a physician, hospital, or other healthcare provider could or should achieve a 100% score on most quality measures. However, there is also no way to know what lower percentage is achievable for the specific population of patients an individual provider is caring for. Value-based payment programs simply assume that a provider with a higher percentage score on a quality measure is delivering better care than a provider with a lower percentage, but that creates an incentive for providers to avoid hard-to-treat patients rather than to deliver better care.

It is not surprising that this flawed approach to quality measurement has failed to improve the overall quality of care and it has likely contributed to disparities in health outcomes for low-income and minority populations.

A Patient-Centered Approach to Evaluating the Quality of Care

How should “high quality care” be defined and measured? High-quality care is patient-centered care, and patient-centered care should have two key characteristics:

- Delivery of Individualized, Evidence-Based Services. Each patient should receive services that can address their specific health problems in a way that is feasible and acceptable for that patient. The starting point in developing a plan of care for the patient should be the services recommended by evidence-based Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs). However, if the patient is unable or unwilling to use those services, deviations from the guidelines will be needed. In addition, when patients have multiple health conditions, guidelines designed for care of individual diseases may not be appropriate, and a customized approach will have to be developed. In order for care to be patient-centered, the patient has to be actively involved in the process of deciding which services they should receive.

- Achieving the Outcomes That Matter Most to the Patient. Regardless of how much evidence there is about how well services have worked for other patients in the past, what matters to the individual patient is whether the services are meeting their specific needs today. The only way for the provider of care to know that is to ask the patient, using a validated instrument such as the What Matters Index. If the patient’s needs are not being addressed, changes to the services must be made. If a patient has multiple problems and it isn’t possible to address all of them effectively, priorities should be based on achieving the outcomes that matter most to the patient.

Two of the key tools needed for this approach already exist:

- Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) have been developed by clinicians for all of the health conditions addressed by typical quality measures as well as many conditions for which there are no quality measures. A CPG assembles all of the available evidence regarding how to diagnose a symptom or treat a condition in a way that is likely to achieve the best outcomes for a patient based on their individual characteristics. CPGs represent a more comprehensive, patient-centered way of guiding high-quality care than a list of narrowly-focused, simplistic quality measures. Although quality measures are generally based either on CPGs or on the evidence underlying the CPGs, the measure specifications ignore the many nuances in the guidelines in order to make the measures easier to calculate, and this leads to the erroneous “quality” ratings described earlier. (For example, current clinical practice guidelines for diabetes say that “an HbA1c less than or equal to 6.5 is considered optimal if it can be achieved in a safe and affordable manner”, but that HbA1c targets “should be individualized based on numerous factors such as age, life expectancy, comorbid conditions, duration of diabetes, risk of hypoglycemia or adverse consequences from hypoglycemia, patient motivation, and adherence.” )

- The What Matters Index (WMI) is a free tool that enables physician practices and other providers to easily identify patients who are not receiving adequate assistance. It is based on a patient’s answers to seven simple questions regarding (1) their confidence in managing their health problems, (2) how much pain they are experiencing, (3) whether they are bothered by emotional problems, (4) how many medications they are taking, (5) whether they believe their medications are making them sick, (6) whether they have enough money to pay for necessities, and (7) whether they feel they are receiving the care they need and want. The WMI has been proven to identify patients at high risk of emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and other problems as well or better than complex risk stratification and predictive modeling systems.

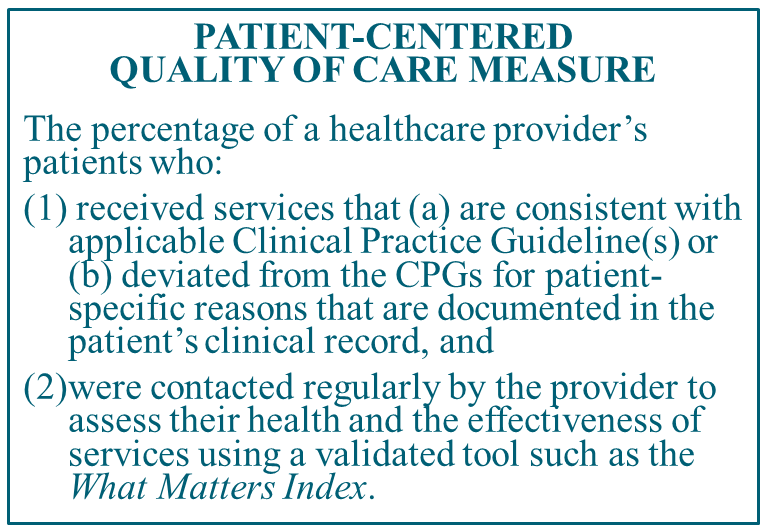

Measuring whether a healthcare provider is delivering care with these characteristics can be easily done without the complex and administratively burdensome systems that are required for current quality measures. When a physician or other clinician orders or delivers services to a patient, they would simply need to attest whether:

- the services ordered or delivered to the patient (a) are consistent with applicable Clinical Practice Guideline(s) or (b) deviated from the CPGs for patient-specific reasons that are documented in the patient’s clinical record, and

- they have monitored the patient’s health and the effectiveness of services using a validated tool such as the What Matters Index.

If both criteria are met, the patient should be classified as receiving quality care. If this approach to measuring quality were used for the four hypothetical patients with diabetes described earlier, Patients 1, 3, and 4 would be rated (correctly) as having received quality care, whereas Patient 2 would not.

If a “quality score” is needed for a population of patients, it is simply the proportion of the patients whose care met the two patient-centered quality criteria.

In contrast to current population-based quality scores:

- Providers can and should achieve a 100% quality score. A provider can and should be expected to achieve a 100% score on the patient-centered quality measure since it explicitly allows services and outcomes to be appropriately customized to each of their patients’ needs. Under this approach, a high-quality provider is one that provides quality care to every patient, not just a higher proportion of patients than other providers. For the two hypothetical physician practices described earlier, Practice A would be rated (correctly) as a high-quality practice, and Practice B would not.

- A single measure can be used by all providers for all of their patients. Instead of the hundreds of narrowly-focused quality measures currently being used in value-based payment programs and the complex attribution and weighting systems used to create composite quality scores, a single, easy-to-understand measure could be used by all providers for all of their patients.

Can payers trust a quality score based solely on what physicians and other providers attest they have done for a patient? They already do. Current quality measures are based on what is reported by physicians, not on information independently collected by payers. For example, the current HbA1c measure is based on the lab test result reported by the patient’s physician; Medicare and other payers do not review patients’ test results themselves or verify the accuracy of the testing equipment. Similarly, the current quality measure for hypertension is based on patients’ blood pressures as reported by their physician, and the measure for depression screening is based on whether the physician attests that a screening was performed. If there is concern that a provider is reporting quality information inaccurately, the payer can audit the provider’s records. The same process can be used in a patient-centered quality measurement system for determining that clinical guidelines were used, that deviations from guidelines were documented, and that providers contacted their patients to find out about their health status and whether their care was effective.

Unlike current quality measures which focus on specific subsets of patients and services and ignore the quality of care for all other patients, patient-centered quality measurement can be used to assure that every patient receives high-quality care, regardless of the specific health problems they have. In addition, because the deviations from current guidelines would be documented in the clinical record and because patient outcomes would be regularly monitored, that information can be used by clinicians to improve the clinical practice guidelines so they support better outcomes and reductions in disparities over time.

The Need for Value-Based Payment That Supports High-Quality Care

A patient-centered approach to measuring quality is necessary but not sufficient to improve the quality of care and reduce disparities. Healthcare providers cannot deliver the services needed for high-quality care if payers do not pay adequately to cover the costs of those services. Merely paying bonuses and penalties based on quality measures, as most current “value-based payments” do, will not remove the significant barriers to patient-centered care that exist in current payment systems. A patient-centered payment system is needed to do this. Details on how to create patient-centered payments are available at PatientCenteredPayment.org.

A pdf version of this article is available for download.