Creating Successful Alternative Payment Models

Steps in Designing a Good APM

In an effort to address the problems caused by current Medicare payment systems, Congress authorized the creation of “Alternative Payment Models” in Medicare as part of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA).

Under MACRA, an Alternative Payment Model (APM) is not just a different way of paying for healthcare services. The law requires that an APM must either:

- improve the quality of care without increasing spending;

- reduce spending without reducing the quality of care; or

- improve the quality of care and reduce spending.

Most of the Alternative Payment Models (APMs) that have been created to date have failed to achieve significant savings or improvements in quality.

It has been asserted that the poor performance of current APMs is because they do not create enough “financial risk” for the participating providers. However, the real problem is that most current APMs do not actually solve the problems with current payment systems and in some cases they make them worse.

Successful APMs can be designed by following a four-step process:

- Identify “potentially avoidable spending,” i.e., specific opportunities for reducing healthcare spending without harming patients;

- Identify or design a different approach to delivering services that is expected to reduce the avoidable spending;

- Create payments that adequately support the new approach to service delivery; and

- Hold the providers receiving the new payments accountable for delivering services in the new way and for reducing the avoidable spending.

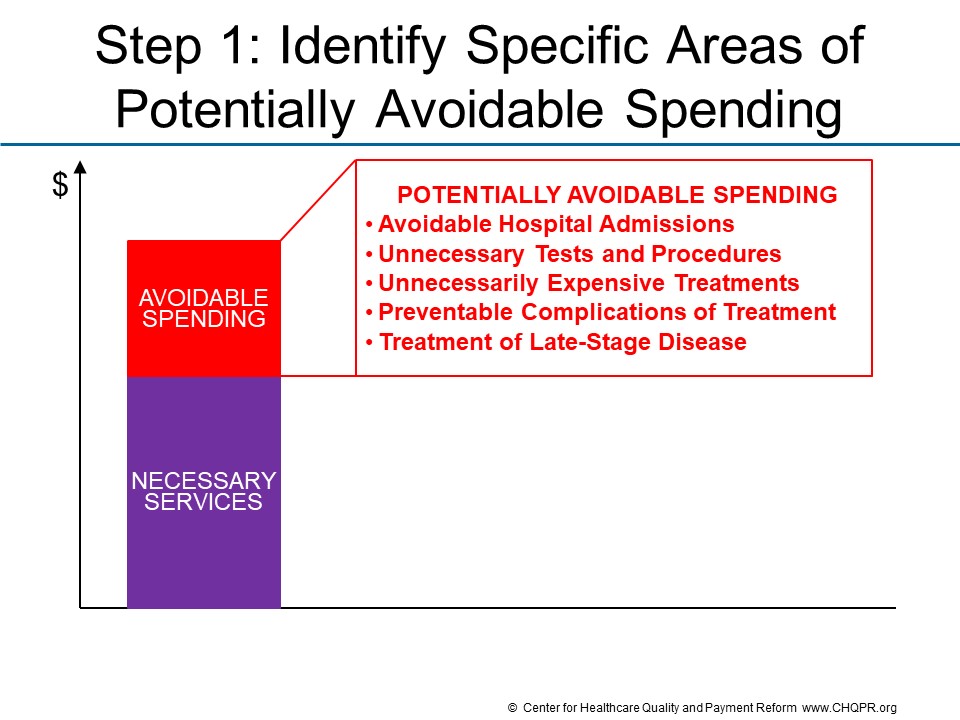

Step 1 is to identify a subset of current spending that is potentially avoidable.

Avoidable spending falls into two major categories:

- Unplanned Care. Avoidable spending in this category includes things such as ED visits and hospitalizations for preventable exacerbations of a chronic disease, preventable complications of treatment, and preventing new health problems from developing. The services are necessary at the time they are delivered, but the circumstances which required the services could have been avoided.

- Planned Care. Avoidable spending in this category includes things like ordering unnecessary tests, medications, or procedures, and also ordering unnecessarily expensive tests and treatments when a less-expensive and equally effective alternative is available. In some cases, the unnecessary services could be harmful to the patient as well as resulting in higher spending.

Although there is a large amount of avoidable spending in the healthcare system, the specific types of avoidable spending will differ for different patients, different health conditions, and different communities.

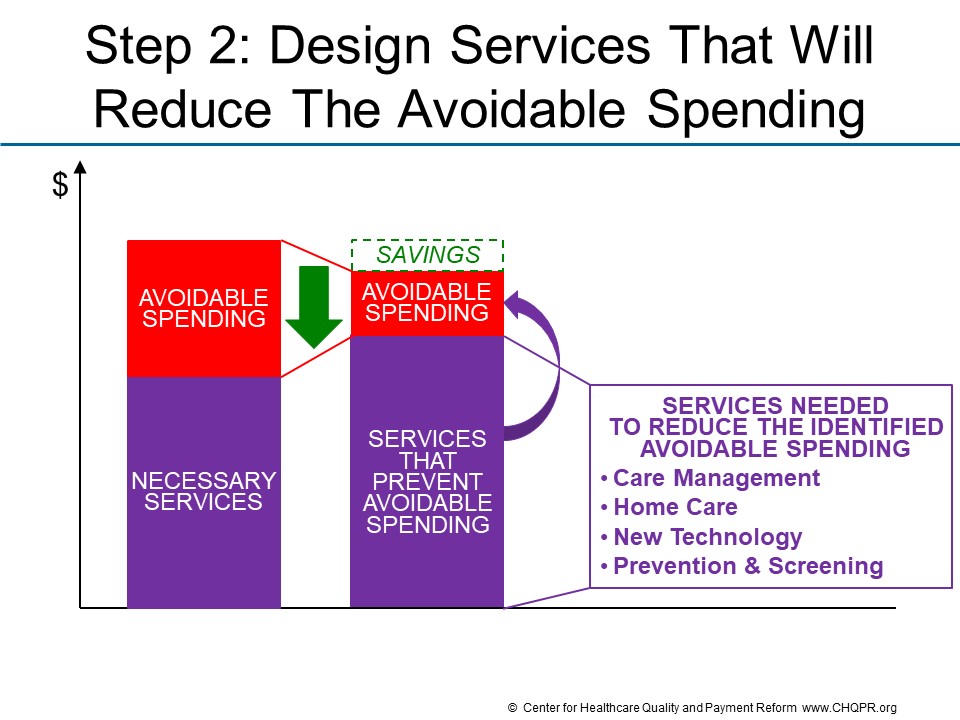

Step 2 is to identify or design a different approach to delivering services that will reduce the avoidable spending.

In most cases, reducing avoidable spending is not simply a matter of delivering fewer services. In general, at least one new or different service must be delivered to a patient instead of the service(s) that will be reduced. For example:

- in order for patients with chronic conditions to avoid the disease exacerbations that result in ED visits and hospitalizations, they may need to receive more education or assistance in managing their condition or they may need different medications or treatments.

- in order for a physician to avoid ordering an unnecessary test or procedure, they may need to spend more time with the patient to narrow the range of potential diagnoses for a symptom, or to help the patient decide to pursue a different method of treatment.

The specific change in services will differ for different types of avoidable spending and different patients.

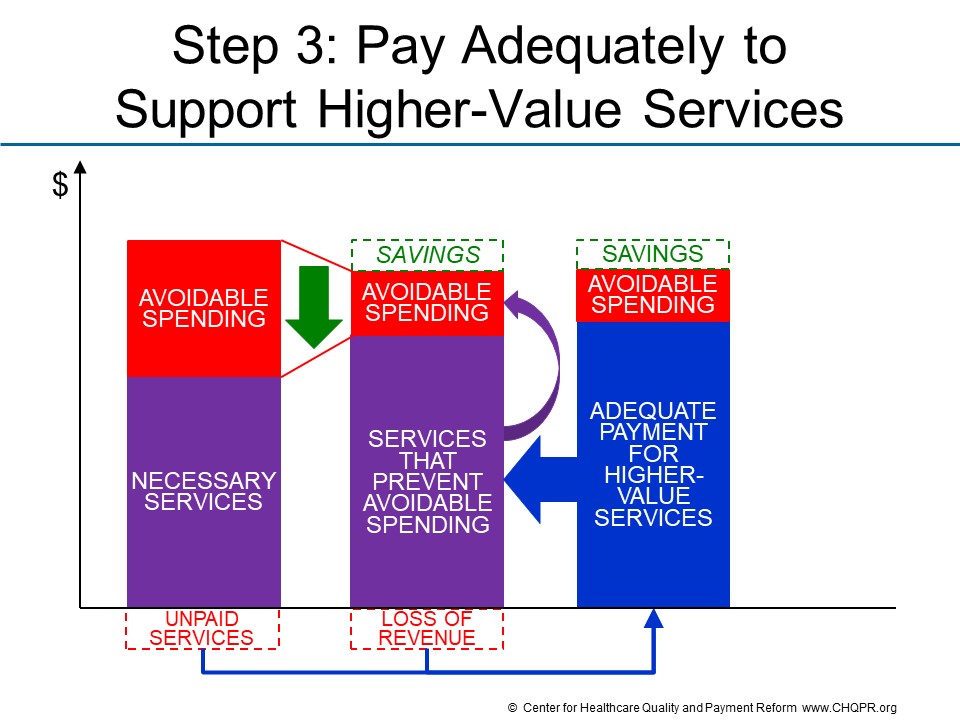

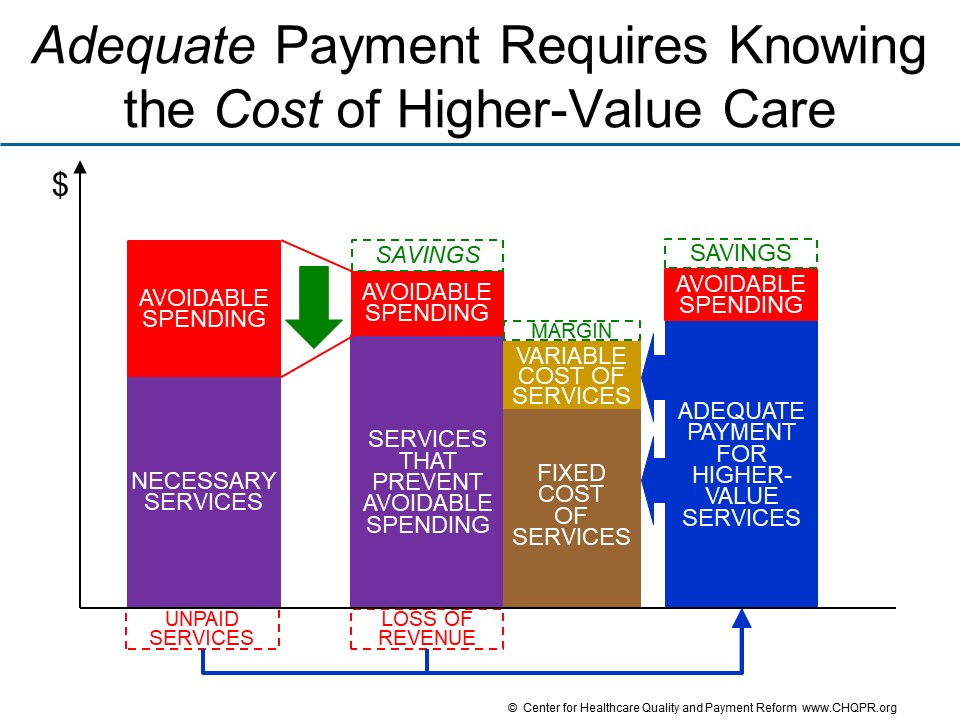

Step 3 is to create payments that adequately support the new approach to delivering services.

When a better approach to care delivery exists and is not being used, it is often because current payment systems create barriers to doing so. These barriers generally fall into two categories:

- No payment for needed services. Even though current payment systems include fees for over 15,000 different services, there are no payments at all for many high-value services that could reduce avoidable spending, such as time spent by nurses educating patients about how to manage their health problems, non-medical services such as transportation to outpatient service sites, and palliative care services for patients with advanced illnesses.

- Inadequate payment for services. For most medical services, a high percentage of the cost of delivering the service is a fixed cost, i.e., it does not change when fewer services are delivered. This means that the total cost of delivering the service does not change in direct proportion to changes in the volume of services delivered, and that the average cost of delivering an individual service will increase when fewer services are delivered. Under fee-for-service payment, however, revenues decrease in direct proportion to volume, creating financial losses for providers.

If the APM does not remove these barriers, physicians, hospitals, or other providers will be unable to deliver services in a way that will reduce avoidable spending.

One cannot expect providers to deliver services in different ways unless payments under the APM are adequate to support the costs of those services. It is impossible to know whether payments will be adequate unless one knows what those services will cost.

The cost of delivering services under an APM cannot be determined from payers’ health insurance claims data for several reasons:

- Claims data has information on what the provider charges for a service and what the insurance plan pays for the service, neither of which may have any relationship to the actual cost of delivering that service.

- Even if the current payment is based on the cost of delivering the service today, that cost may change if the service is delivered more or less frequently in order to reduce avoidable spending.

- If the payer does not pay for the service, it is unlikely to be delivered at all.

Cost accounting systems and methodologies such as Time-Driven Activity-Based Costing can provide information on what it currently costs to deliver current services, but not what it will cost to deliver care differently in the future. A Cost Model is needed that identifies the fixed costs, semi-variable costs, and variable costs associated with the services and makes estimates of how those costs will change when there are changes in the number or types of services delivered.

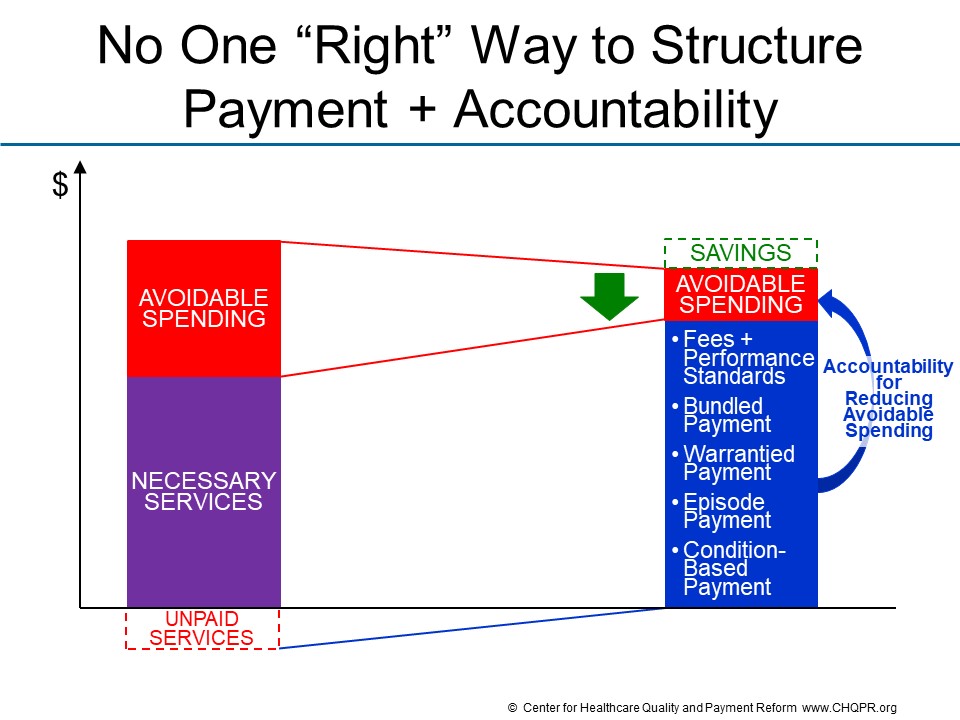

Step 4 is to hold the providers receiving the new payments accountable for delivering services in the new way and for reducing the avoidable spending.

If the payments created in Step 3 eliminate or adequately mitigate the barriers that exist in current payment systems, it should be feasible for patients to receive services in the way defined in Step 2, which in turn should reduce the types of avoidable spending identified in Step 1. Consequently, it is reasonable for the payer and patient to expect assurance that a healthcare provider participating in the APM will, in fact, deliver services differently in order to achieve the desired results.

There is no one “right way” to structure an APM so that it both provides adequate payment and ensures appropriate accountability. There are several different approaches that can be used, including:

- Fees + Performance Standards. In many cases, all that is needed is to pay fees for new services and/or higher fees for existing services, and to require that certain performance standards be met in order to receive those fees. (This is different than current approaches to “pay for performance” in which no changes are made to what is paid for individual services.)

- Bundled Payment. A single “bundled” payment for a group of related services can provide flexibility to substitute lower-cost services for higher-cost services when appropriate.

- Warrantied Payment. In a warrantied payment, there is no additional payment for services delivered to address complications or other avoidable healthcare problems.

- Episode Payment. An episode payment is a bundled and warrantied payment for all of the services that occur over a period of days or months as part of a specific procedure or treatment.

- Condition-Based Payment. A condition-based payment is a bundled and warrantied payment for all of the services that are needed to fully address a specific health problem (either an acute condition or a chronic condition).

The appropriate approach will depend on the types of health problems being addressed, the types of services needed, and the types of providers and patients involved.

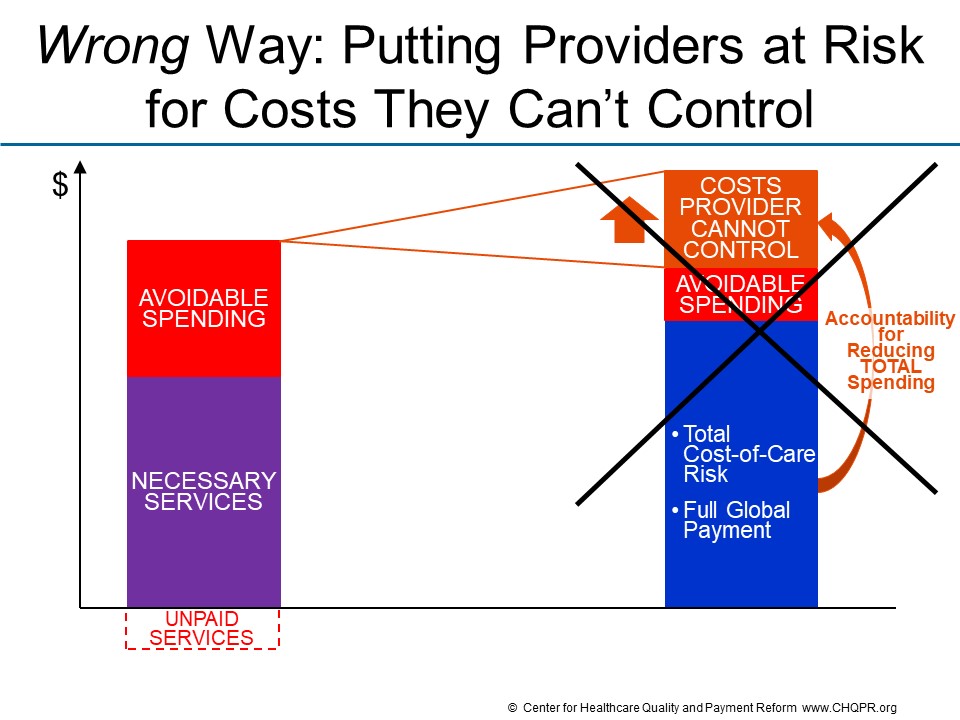

Although there is no one right way to hold healthcare providers accountable for results, there is a wrong way to do so, namely putting providers at financial risk for aspects of services and costs they cannot control.

The APMs created by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and other payers attempt to hold providers accountable for total healthcare spending on their patients, even though providers cannot control all of the services their patients receive or the costs of many of those services. For example,in CMS APMs, physicians can be penalized when there are increases in the prices of drugs that their patients receive even though physicians have no control over what pharmaceutical companies charge, and a specialist treating one health problem can be penalized for services ordered by a different physician who is treating an unrelated condition. Moreover, these APMs can increase disparities in healthcare access and outcomes by penalizing physicians when they care for sicker and more complex patients.

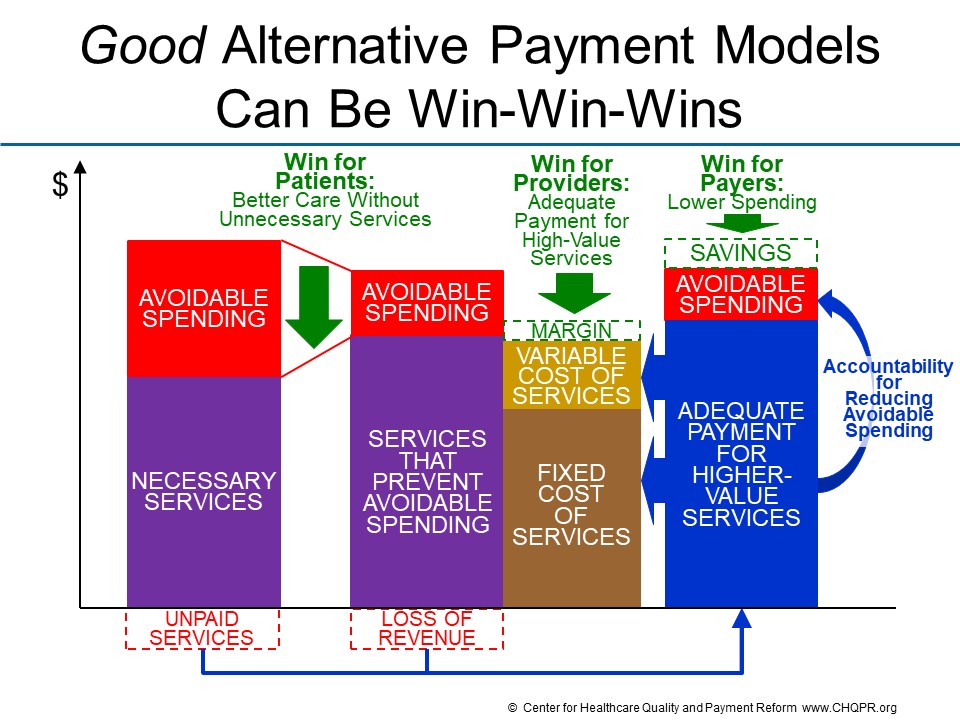

If it is designed properly, an Alternative Payment Model can and should be a “win-win-win” for patients, providers, and payers:

- Patients win by receiving the care they need to address their health problems, not receiving unnecessary or avoidable services that are expensive or harmful, and avoiding complications and other undesirable outcomes.

- Providers win by being able deliver the services their patients need. They do not lose money by delivering high-quality care nor do they make higher profits by delivering unnecessary services or allowing preventable complications to occur.

- Payers win by paying no more than is necessary in order for patients to receive high-quality care, enabling them to offer insurance at the most affordable cost.

The best approach to an Alternative Payment Model is Patient-Centered Payment.

© Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform www.CHQPR.org

Sharing Risk Appropriately in APMs

Most of the Alternative Payment Models (APMs) developed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have been designed to place healthcare providers at risk for total healthcare spending on their patients. However, no individual healthcare provider can control total healthcare spending on their patients. Moreover, since a small percentage increase in total healthcare spending can represent a large percentage of the APM participant’s revenue, there is the very real possibility that participating in these APMs could bankrupt small healthcare providers. As a result, many providers have been unwilling to participate in CMS APMs.

Unwillingness to accept such large and uncontrollable risk does not mean that healthcare providers are unwilling to accept any risk at all. Contrary to popular belief, there is significant financial risk for healthcare providers under standard fee-for-service payments: there is no guarantee that the fee they are paid for a service will be greater than the cost of delivering that service, particularly if the volume of service delivery is not high enough to cover the provider’s fixed costs. However, unlike CMS APMs, fee-for-service payment does not place providers at financial risk for whether their patients develop a new health problem or receive services from a completely different provider.

To be successful, an Alternative Payment Model needs to transfer only appropriate components of financial risk from payers to providers.

The starting point for appropriate risk sharing is to define the amount providers will be paid under the APM based on two separate things:

- how much payers are expected to save if they no longer have to pay for the specific types of avoidable spending that providers plan to reduce; and

- how much providers expect it will cost to deliver the services required to address patient care needs and to reduce the avoidable spending.

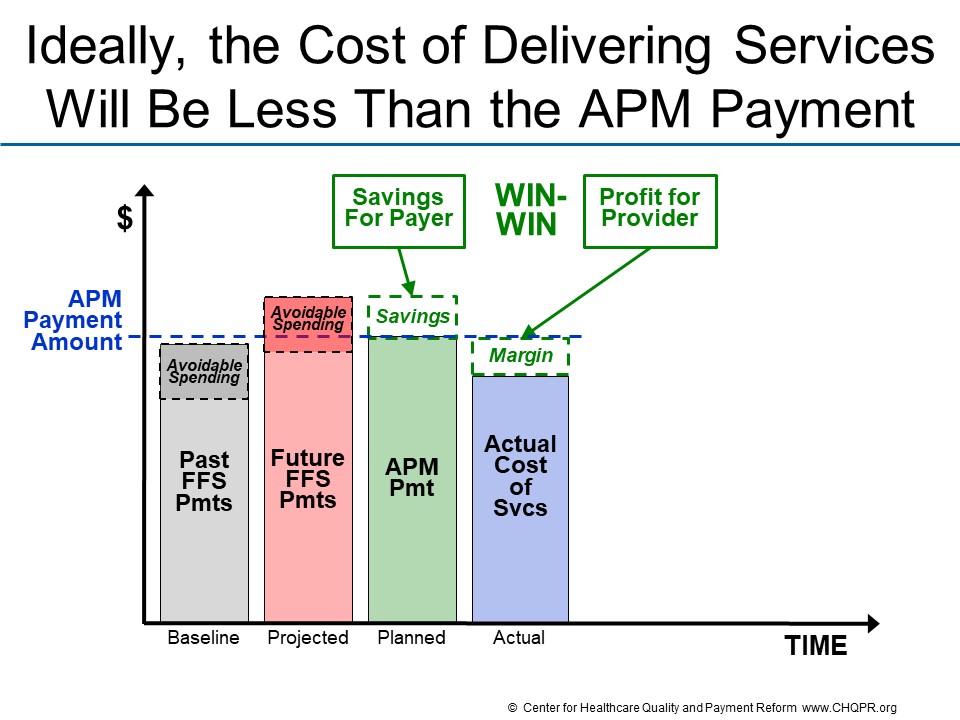

If the expected cost of delivering the services that patients need is less than the amount payers are currently spending on services to those patients, there is an opportunity for a “win-win” for payers and providers. The payment amount under the APM can be set at a level that generates savings for payers while also providing a positive financial margin for providers.

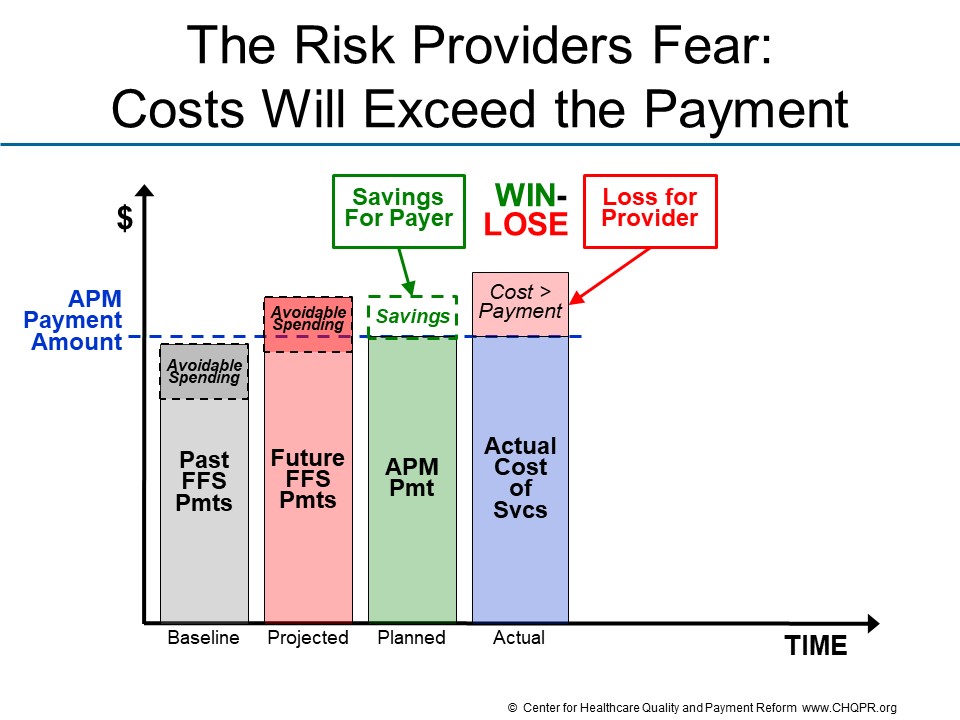

What providers fear is that the actual cost of delivering services will be higher than expected, or higher than the amount payers actually pay.

Under this scenario, the payer could still “win” financially if the APM payment is less than what the payer would otherwise have expected to spend on the services the patients need or receive. However, the provider would experience a financial loss if they have to incur the costs of delivering the services without adequate payment to support those costs.

Many CMS APMs set the APM payment amount by applying a “discount” to the amount that CMS expects it would otherwise spend under standard fee-for-service payments, without regard to whether that amount will be more or less than the cost providers will incur to deliver the services. Although this is designed to guarantee Medicare will “win” under the APM, the win will merely be theoretical if providers refuse to participate or go out of business because they are not paid adequately.

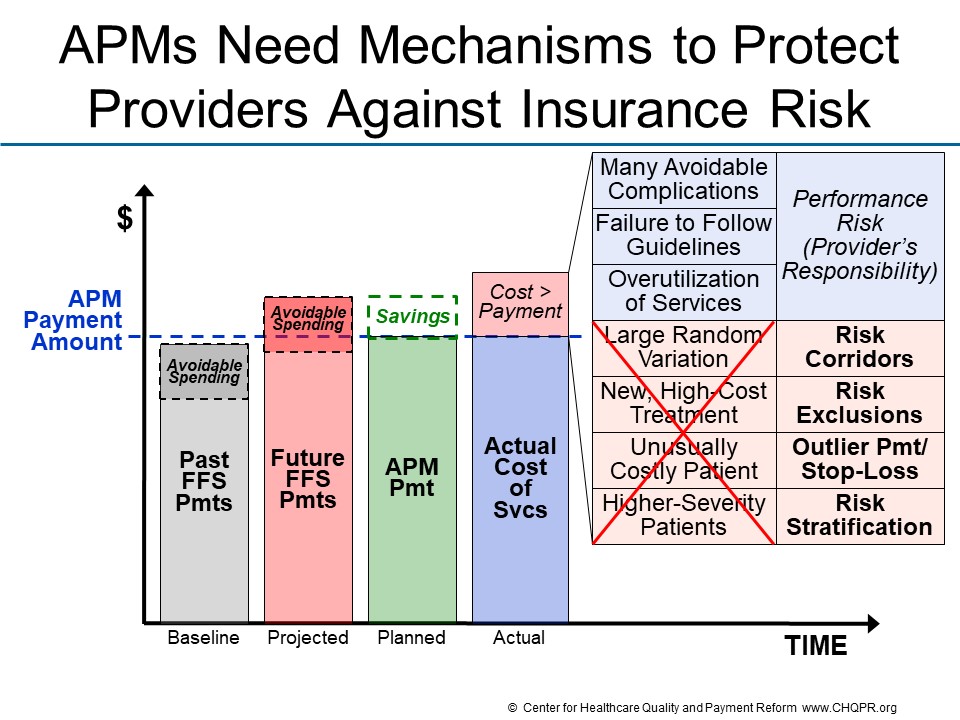

Assuming that a good faith effort has been made to set the APM payment so it produces savings for the payer while avoiding losses for the provider, there are two fundamentally different categories of reasons why the cost of delivering services can increase over time or exceed the amount that providers or payers projected:

- Performance Risk. Costs may be higher due to factors that the provider was able to control. For example, the provider may have delivered treatments in a way that resulted in many avoidable complications, or the provider’s patients may have developed health problems that could have been prevented by following evidence-based guidelines, or the provider may have simply ordered unnecessary services. In these situations, the physician, hospital, or other provider has performed poorly, and it is appropriate for them to incur a financial loss as a result. Accountability for controlling these types of factors can be described as “performance risk.”

- Insurance Risk. On the other hand, costs may be higher due to factors the provider was not able to control. For example, if the providers’ patients have more health problems, more severe health problems, or more complex needs that require delivering a large number of services or very expensive services, the costs incurred by the provider in treating the patients will be higher, but the higher cost is not something that the provider could or should be able to reduce. If medical research results in a new treatment that is significantly more effective in treating a patient’s illness. the patient should receive that treatment, but if the treatment is more expensive than existing therapies, the cost will be higher. These types of situations can be described as “insurance risk” because they are precisely the kinds of unpredictable events for which one purchases insurance.

An APM should be designed to address these two types of risk in different ways:

- The APM should hold providers responsible for performance risk.

- The APM should protect providers from insurance risk.

There are four different components that can be included in APMs to protect providers from different types of insurance risk:

- Risk Corridors: The amount of payment should be increased if spending on all patients exceeds a pre-defined percentage above the total payments received under the APM. An alternative would be for the APM to pay the provider enough to purchase aggregate stop loss insurance.

- Risk Exclusions: Services the provider does not deliver, order, or otherwise have the ability to influence should not be included as part of accountability measures in the payment system. The payment should be adjusted for changes in the prices of drugs or services from other providers that are beyond the control of the provider accepting the payment.

- Outlier Payment: The payment should be increased if spending on an individual patient exceeds a pre-defined threshold. An alternative would be for the APM to pay the provider to purchase individual stop loss insurance (sometimes referred to as reinsurance).

- Risk Stratification: The payment rates should vary based on objective characteristics of the patient and treatment that would be expected to result in the need for more services or increase the risk of complications.

© Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform www.CHQPR.org